an article by Arlette Dumon du Voitel.

Humans – success or failure factor in projects?

Accepting humans as humans isn’t always as easy as it sounds.

Humans drive us crazy in any private or professional relationship. This isn’t different in project management. Who hasn’t been frustrated with their sponsor, client or a team member? Who hasn’t delegated a task and received a result that was below expectations? Who hasn’t experienced that people made mistakes on projects although we did everything to avoid it?

In light of this, is it correct to speak about „The human success factor in projects“ as we recently did at the PM Summit of the Project Management Institute PMI® in Munich? When I talk to people who are working in projects, I gain the impression that PMI® got the title of their event all wrong.

Humans are much rather the “failure factor” than the “success factor” as they don‘t listen, they forget, they make mistakes and so on.

AI – the better alternative to flawed humans?

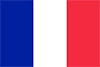

Luckily there is a relatively new guy in town and he / she / it is perfect! Artificial intelligence is – as I understand – still in its infant state but it can already so much more and so much more reliably than us. They paint like Vincent Van Gogh, write music like Mozart, write books that are shortlisted for awards as well as analyse and evaluate complex data sets as fast and accurate as none of us.

Most of us would struggle to do these things. But our biggest drawback in comparison is, however, that we are full of flaws. And this is exactly the challenge we are faced with in projects. Humans are our main „production factor“ and they just don‘t seem to function properly even if they are skilled or talented like Mozart or Van Gogh. The stereotypical artist is the best example: they tend to be able to create something extraordinary while driving their managers, customers, fans, families and friends absolutely insane in the process.

In projects we are dealing with a lot of these artists – only that we call them experts. And we deal with even more „ordinary, normal people“. People who are intelligent and have at least the potential to do a good job but it requires effort to get them there.

Homo Oeconomicus – a human misconception:

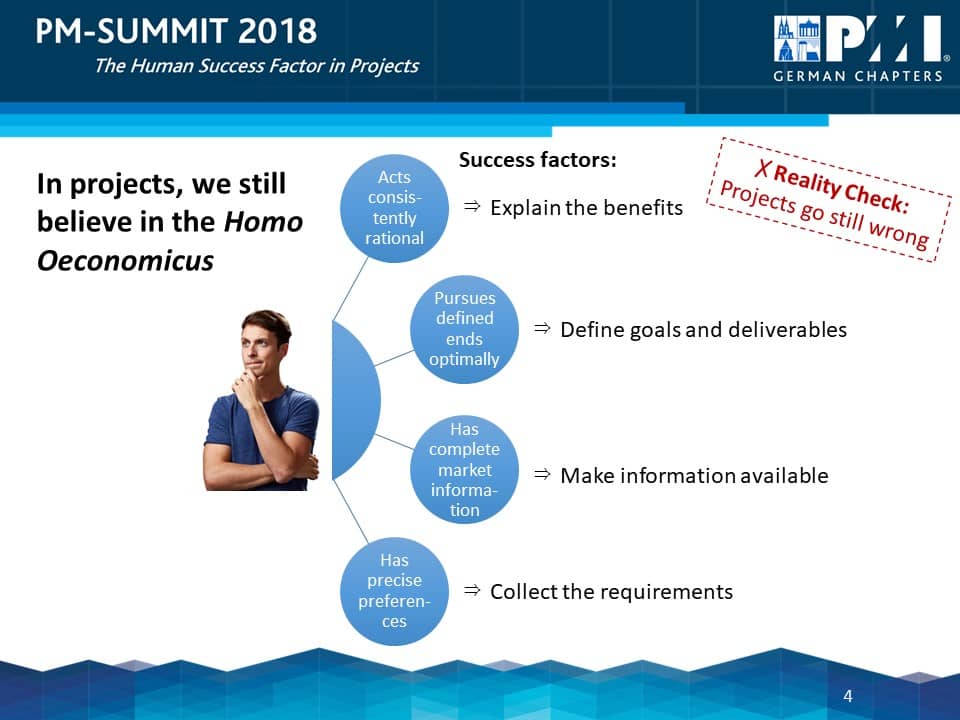

We have noticed this a long time ago and we come up with models to explain human behaviour in order to find that lever to get them to function. Possibly one of the simplest, least accurate and most ineffective models is the so-called „Homo Oeconomicus“.

The „Homo Oeconomicus“ is a model of human behaviour used in some if not most economic theories, in particular when it comes to decision making. It is based on the belief that humans aim to maximise their utility.

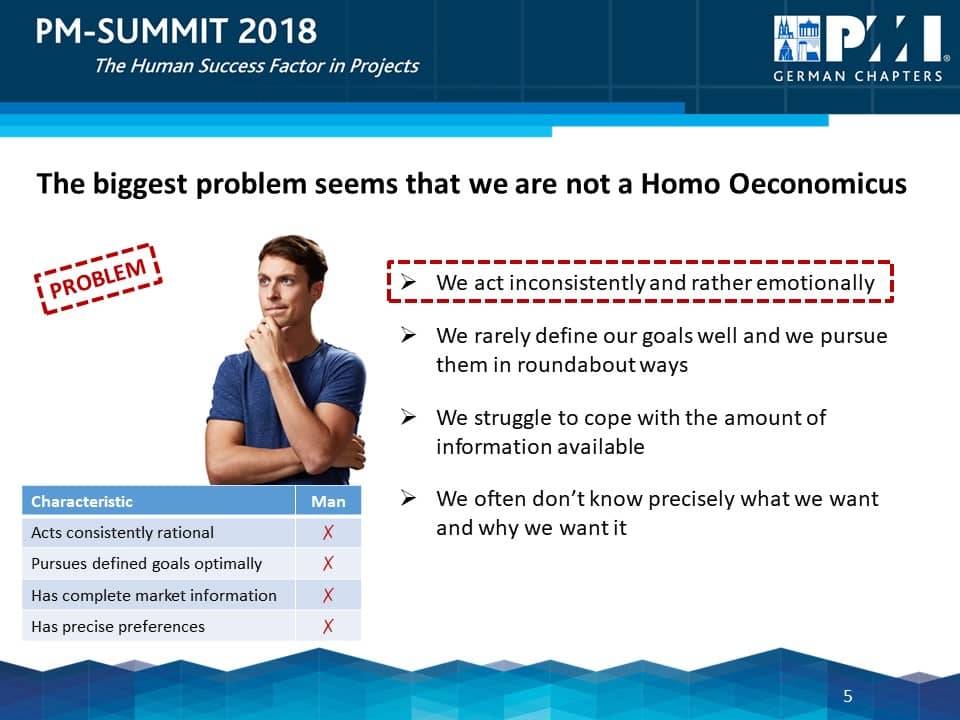

4 key criteria characterise human behaviour in this model – the „Homo Oeconomicus“:

– acts consistently rational,

-pursues defined ends optimally,

-has complete market information

-and has precise preferences.

But regardless of whether or not we believe in this model, we still seem to apply it. People keep expecting “professional behavior” in “professional environments” and are surprised if a “professional” reacts emotionally. We seem to believe that we can leave our emotions at home when we go to work and switch on our rational self as soon as we walk through our office door. But the truth is that most people don‘t have a split personality. We act just as human in professional environments as we do in private ones.

Nevertheless, in project management, we cater for the „Homo Oeconomicus“: as we expect rationality in a professional environment, we explain the project’s benefits to the stakeholders and expect that they understand and welcome the benefits. We believe that our team members will pursue the defined ends optimally as long as we define the goals and deliverables well enough. We make information available to stakeholders so that they have complete information and are able to act rationally. And we expect them to know their preferences when we collect their requirements. At the end of the day, we are surprised that none of it lived up to the expectation.

Daniel Kahneman, a very well-known Israeli-American psychologist and Nobel laureate, has proven through many experiments that the „Homo Oeconomicus“ is a myth and human behaviour is almost perfectly opposed to the model: we act inconsistently and rather emotionally, we rarely define our goals well and we pursue them in roundabout ways, we struggle to cope with the amount of information available and we often don’t know precisely what we want and why we want it.

So the suggestion here is that rather than trying to squeeze humans into a model that doesn‘t correspond to their nature at all, we should accept humans for what they are and find a way to work with it. But unfortunately, this means that there are no simple recommendations.

Human behaviour – what we know about it:

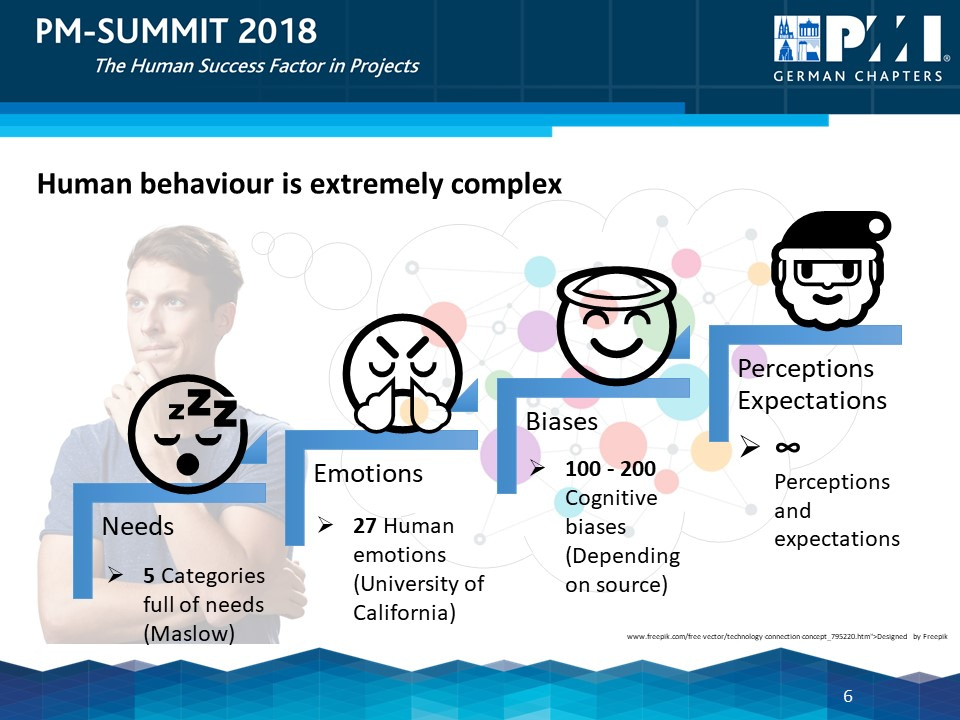

Human behaviour is extremely complex and an area that we still don‘t fully grasp. Maslow alone identified 5 categories full of individual needs. The University of California claims that there are 27 human emotions. Depending on the source, there are somewhere between 100 and 200 cognitive biases and no one dares to put a number on the possible perceptions and expectations that may result out of each and every personal history.

Think about the number of possible cocktails that might result out of these ingredients. We deal with our own cocktail as well as the cocktails of our surroundings everyday. Considering this, it is actually a miracle that we have made it so far as a human community and that so few things go wrong. So there is already a first healthy change of perspective.

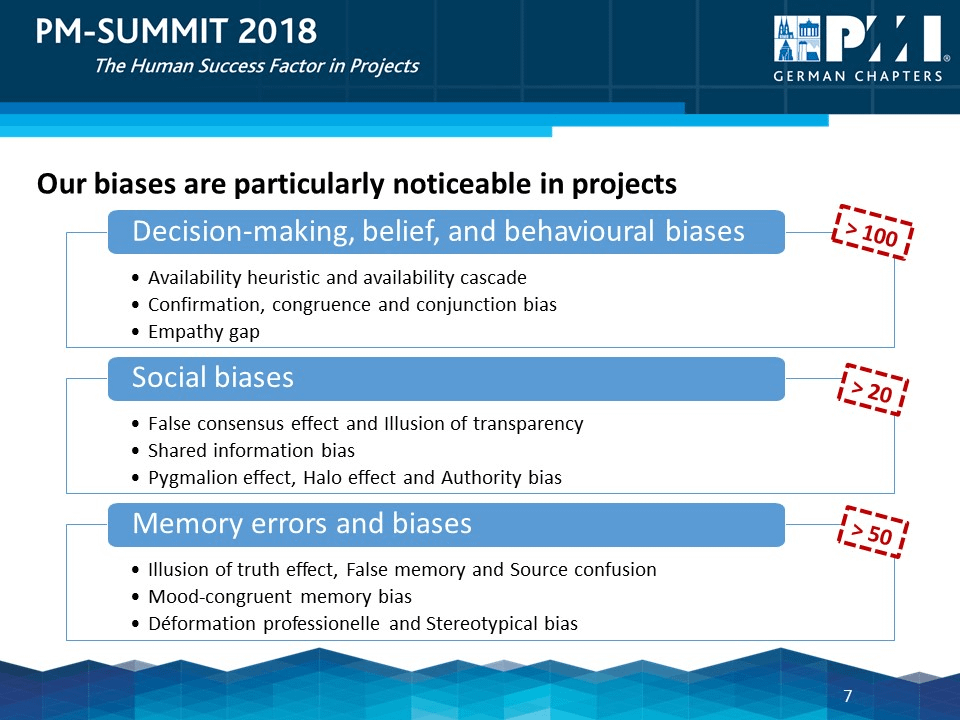

Cognitive biases in particular are quite prominent in projects and can explain a lot of phenomena that we observe in projects. A cognitive bias is a systematic error in our thinking processes and a mental shortcut in order to save mental processing time and energy when making a decision. It affects the way we perceive, assess and remember things. As a consequence, we often make mistakes, bad judgment and wrong interpretations that lead to misunderstandings.

There is, for instance, the availability heuristics and availability cascade biases: things we have heard or read recently are more prominent in our memory than other pieces of information – since they are more „available“, we attach greater meaning to them. For example, since the media report almost solely on disasters, most people judge the likelihood of dying in a terrorist attack or plane crash as higher than through, for instance, bad lifestyle choices – although the latter is a common cause of death and the other highly unlikely.

In addition, if something is repeated often and long enough, it will become true. So the availability heuristic is reinforced by the so-called availability cascade.

In project management, these two biases have a massive impact on our risk management – among other areas. Most normal, non-life-threatening projects perform their risk identification and assessment entirely on the grounds of availability heuristics and cascade. We ask our team what risks they see, how likely they think it is to occur and how high the impact would be if it was to occur – and voilà, we have our rating. We usually don’t look into actual statistics. As a consequence, we end up being surprised by risks that we didn‘t see coming or we deemed unlikely while risks that we feared and monitored closely never materialised.

The „false consensus effect“ refers to the fact that we tend to overestimate the extent to which others share our beliefs or opinions. If we think that something is normal, good or beneficial, we assume that others share the same view. In addition, the „illusion of transparency“ describes that we tend to overestimate how aware others are about our mental state of mind. We think that people should be able to „see“ that we are tired, sad, angry, hurt or whatever the case may be.

Truth is: others can‘t read our minds – and we can‘t read theirs. But this is exactly how we lose our stakeholders and nurture conflicts in projects.

And one last example: The Pygmalion effect creates self-fulfilling prophecies – good or bad. Experiments have shown that if we tell people that they are talented in an area they are likely to perform very well in this area whereas if we – for instance – tell girls from early on that they are bad at maths, this is also going to be the case.

In projects, the Pygmalion effect leads to the following phenomenon: As project managers, we usually believe that we are the most useful and competent person in regards to the project. As a consequence, we end up doing the lion share of the work because nobody else can do it as well as us. In addition, we usually need to rework the work we delegated and we have to deal with sabotaging and counterproductive stakeholders.

To a large degree, this is the Pygmalion effect – it‘s a self-fulfilling prophecy we created. Since we believe that we are the only ones able to do the work right, we are going to be the only ones who can do the work right. We adapt our entire behaviour to suit our belief. We stop communicating properly, monopolise information, stop delegating, trusting, sharing – and we drive people away who could have helped us.

If we changed our perspective on us, our team and stakeholders – if we perceived them as just as or even more valuable to the project than ourselves, we could turn the self-fulfilling prophecy around and use it to reduce our own workload and to engage team members and stakeholders very effectively.

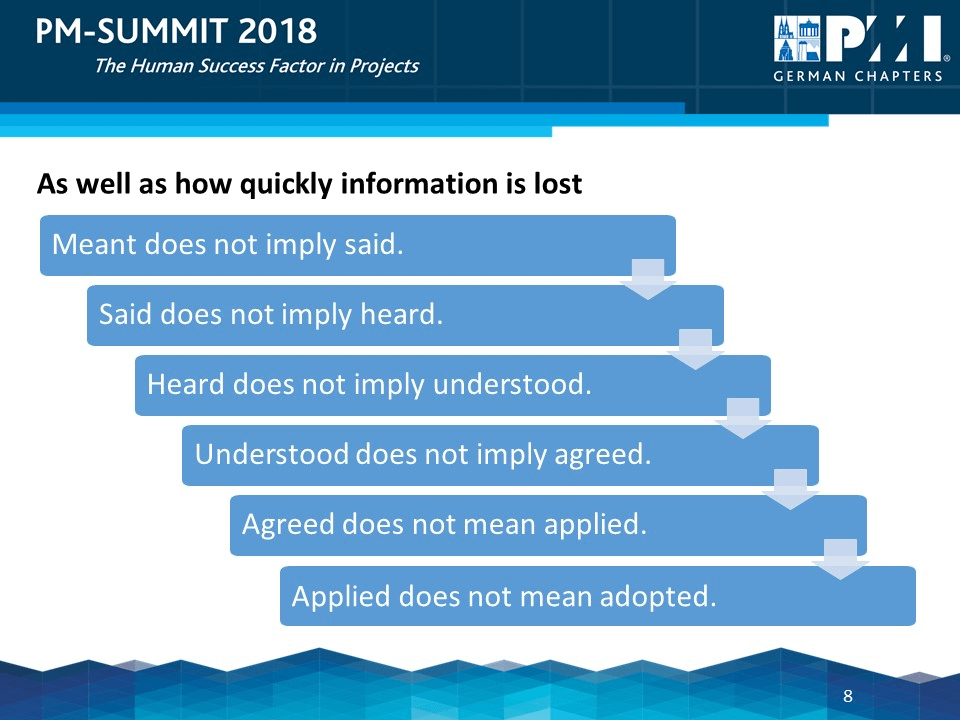

Along with the cognitive biases goes our expectation that if we said something, this should result in the adoption of a specific behaviour by the person we addressed. But meaning to say something doesn’t imply we said it. Having said something doesn’t imply the other party heard it. Hearing the message doesn’t imply understanding it. Understanding it doesn’t imply agreeing to it. Agreeing to it doesn’t imply applying it and finally applying it once doesn’t mean adopting a behaviour long term.

This so-called „staircase of information loss“ doesn‘t only show how quickly information is lost – it also helps us to communicate better, practice better „active listening“ and identify where communication went wrong if it did. So rather than in frustration over the other person who „didn‘t listen again“, we can invest our energy in fixing the communication problem.

Humans as success factor – the requirements:

So, if „accepting humans as humans“ is the requirement for humans to be the success factor in projects, this means that we need to accept the flaws, the needs, the emotions, the biases, expectations and perceptions – and deal with them instead of ignoring or fighting them and getting frustrated as a consequence.

As a consequence, the project manager really needs to spend this 90% of his or her time communicating as we learn in preparation for the PMP® certification. In this context, communicating doesn’t mean writing reports and sending emails with everyone in cc but trying to understand the different cocktails we have in our teams and among our stakeholders, testing and correcting hypothesis. It means trying to be in touch with people as much as possible to get feedback and to see whether communication is working or needs to be adjusted.

Investing time in humans – is it worthwile?

As this all sounds and is awfully complicated, let’s quickly go back to the new alternative who would actually tick all the boxes as „Homo Oeconomicus“ for which we seem to have a working model that is easy. Wouldn’t AI rather qualify as success factor in projects?

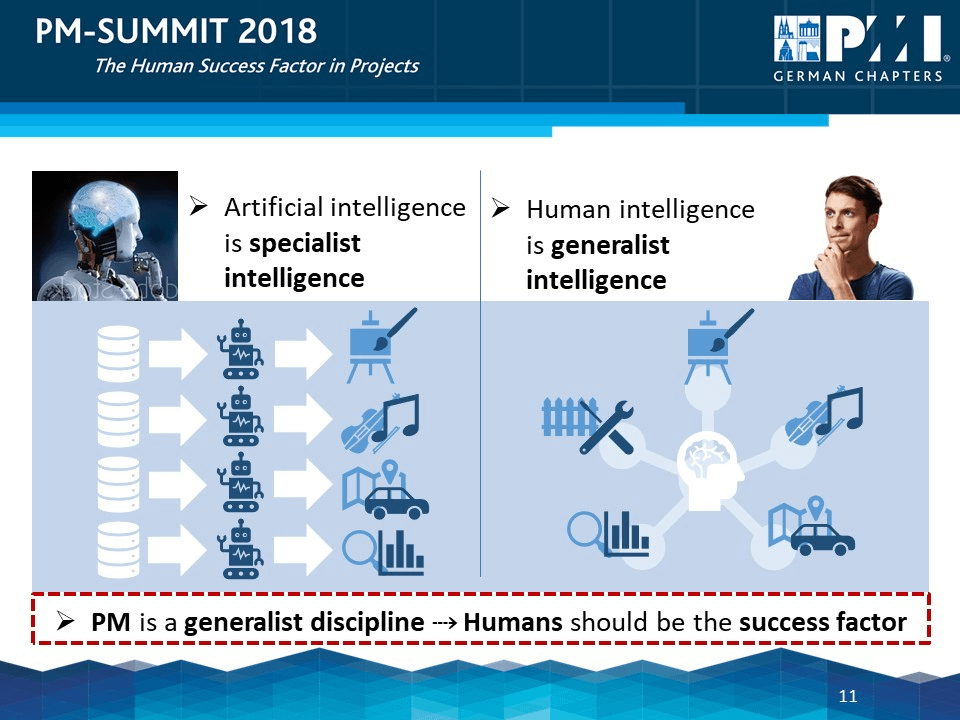

One of the key reasons that is always mentioned when AI experts are asked if humans will still play a role in the future is: AI is a specialist intelligence. It can outperform us in almost any specialist area.

But: If it is taught to paint like Van Gogh, it can do this amazingly well but it can‘t finish Mozart‘s Requiem or drive us home at night. So, humans still outperform AI as generalists. We can paint a little, at least sing along the radio, drive savely enough to get home – we can even sing while driving! And we are able to make connections between different areas, we can observe, reflect, understand how one thing might affect another.

For projects, this is extremely relevant. Project management is a generalist discipline. Per definition, projects create something new that has never been done before. They have a goal, a purpose and fulfill a need. This goal, purpose and need is for the benefit of (at least some) humans.

As project managers, we don‘t have to be a specialist in any particular area. But we need to be a very good generalist who has enough working knowledge to talk to specialists as well as to other management functions, such as finance and controlling. We need to be able to connect the dots – to perform integration. This is also true for sub project managers, team or work package leaders, agility masters etc.

So for the time being, AI is a fantastic opportunity rather than a threat to the profession of project managers. AI may be a fantastic addition to the team or assistant to us, in particular in the areas where it outperforms us and/or where our greatest flaws and biases are. Accepting humans as humans is also understanding in what areas we shouldn‘t trust ourselves and where we need help – also in form of technology. If an AI is able to screen billions of statistics in no time and produce an estimate and recommendation based on actual occurrences rather than our availability heuristics than this is really good news, for instance in risk management. It will be more accurate than our gestimation and take less time – time that we can instead spend on leveraging the human success factor.

Invest now and gain later – why it works:

Leveraging the human success factor, as already mentioned, starts with accepting humans as humans with all their inconsistencies, emotions, biases, flaws but also the fact that there is no easy 5 step model on how to recognise and deal with the cocktail that we are confronted with at any particular moment in time.

Why is this important? Because we waste way too much time and energy in frustration about the fact that we are and we are surrounded by humans. Remember the Pygmalion effect: If we changed our perspective on human behaviour, if we took human flaws with a good sense of humour and laugh at the irony of them, if we started to appreciate the fact that although we are these difficult and different creatures, we enjoy being around each other and do get amazing things done (after all we invented AI!), we would not only feel less stressed but also nurture a positive self-fulfilling prophecy.

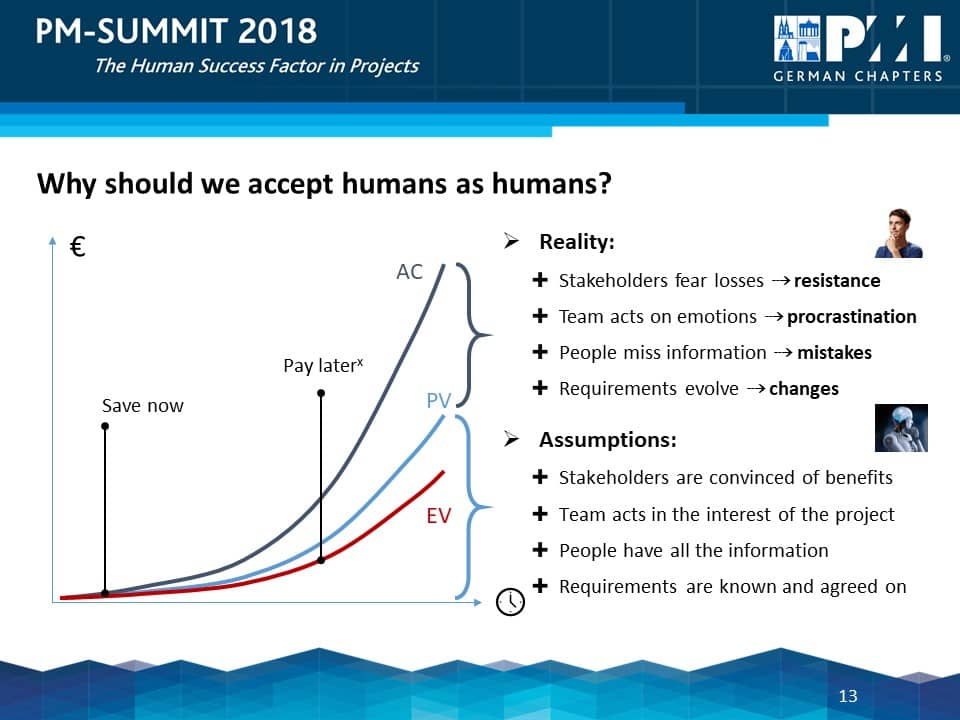

This was the soft answer to why we should accept humans as humans. But this can also be backed with some hard facts. Planning is trying to predict the future – it has to be based on assumptions. As we know: Assumptions are uncertainties and uncertainties are risks that cost time and money if they occur. The most common implicit assumptions are once again closely related to the „Homo Oeconomicus“ concept:

We believe that people (should) act professionally and rationally in work environments, so stakeholders can be convinced of the benefits. We don’t cater for the likely risk that they might appreciate the benefit but still don’t want the change that the project brings about. The „false consensus bias“ lets us set this risk to „0“. But in reality, humans like benefits but they fear losses even more (loss aversion bias) so we are faced with resistance. This is normal. So we should much rather assume resistance than consensus even if the benefits are clear.

We believe that teams pursue the defined ends optimally. But even if they fully support the interest of the project, they will act on their emotions.

We prefer easy tasks and delay hard ones (usually the important ones) so procrastination delays completions. This is a risk that never shows up on a risk register.

Information may be fully accessible but it also gets lost and mistakes are made – remember the staircase of information loss. We have to rework and fix things.

Stakeholders preferences were not set in stone as assumed, so we are faced with changes.

All of these paired with a little bit of bad luck here and there lead to the fact that actual costs soar, we are delayed and earned value underperforms.

Essentially, we decide to save time and money during planning by applying a simple model about human behaviour rather than preparing for the complexity of human behaviour. As a result, we implicitly decide to pay later during executing when the model falls through because it is incorrect.

The issues is that by then problem-solving is complicated, stressful, time-consuming and very costly.

Therefore, accepting humans as humans should be seen as an investment. I invest and allocate time and money in order to cater for human behaviour. I anticipate different scenarios. I adjust my expectations. I integrate it in my risk management. I monitor the behaviour and feedback. Instead of „saving now and paying later“, I „invest now“ and “gain later“.

Change it or leave it – the choice is ours:

To sum it all up, we have two choices:

1- We can continue the way we are going and work with models on human behaviour that are provenly incorrect. We can still use them in order to save now (during planning) and pay later (during executing). We can spend time and energy into being frustrated with the fact that our team members, sponsors, clients, suppliers don‘t function although they should. And we can thus nurture a negative self-fulfilling prophecy.

2- Or we can start changing our perspective by accepting humans for what they are. We can invest in trying to get communication right. We can save our nerves if communication goes wrong nevertheless by accepting that this is normal and reinvesting time to understand why it went wrong and to fix it. We can appreciate the fact that although there are so many people (and their cocktails) involved, we manage to achieve great things in particular through projects and that people – team members, sponsors, clients, suppliers, stakeholders in general – are useful to us in many different ways. And, hence, we can turn the self-fulfilling prophecy in a positive direction.

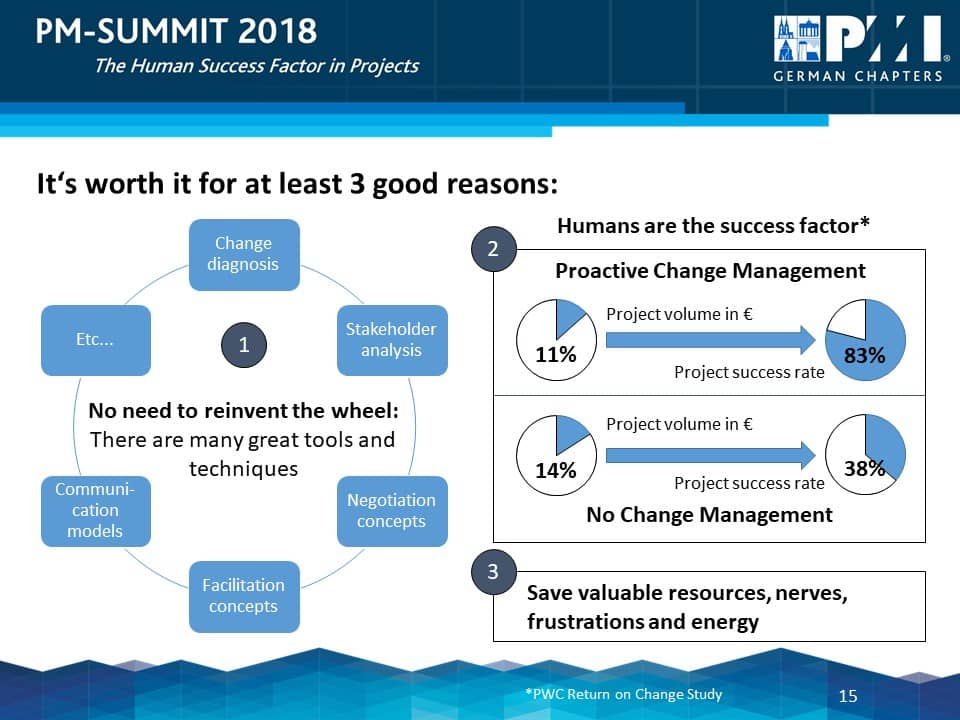

The latter option is worthwhile for at least three reasons.

To start with: We don’t need to reinvent the wheel. There are so many fantastic tools and techniques in change and project management that we only need to apply properly.

Secondly, there is evidence that applying these tools and techniques properly (investing now) ends up being cheaper for a project and increases the likelihood for success from 38% to 83% (gain later)*.

And maybe most importantly, it saves us valuable resources, energy, nerves and frustration.

*PWC Return on Change Study, 2012

And you, what do you think? Do you think that Humans can still compete against Artificial Intelligence in project management or should we just accept that we will soon be obsolete?

We would be thrilled to read your comments on this topic!